interview

To identify with the sound

An interview with Ashish Sankrityayan

After a concert and workshop in Lund in February 2006, Johan Laserna had a conversation with dhrupad singer Ashish Sankrityayan about his art.

JL :: Yesterday, at the concert, you gave a brief description of dhrupad and dhrupad singing. I would now like to ask you a few questions, of a more personal nature, to add some details to the picture. What made you, initially, want to explore dhrupad? I know that dhrupad is not a part of your heritage, you did not learn it by being a member of a dhrupad family, so what made you want to become a singer in this ancient tradition?

AS :: I actually started learning classical music at a very young age, already in my childhood. I first learned the sitar, for four or five years, then I completely stopped and did not pick up music again until university, when I started singing. This was a different kind of singing, not dhrupad, called khayal. Throughout my childhood I heard about something called dhrupad, and that there existed a certain Dagar family which practised dhrupad. My father even showed me pictures of members of the Dagar family in the magazines, and explained to me that they were the most famous dhrupad singers, but I never actually heard dhrupad.

JL :: But was their reputation favourable, was there anything in it that attracted you?

AS :: Well, my father told me that they practised this, and that it was very old and that they used pakhwaj instead of tabla. He had heard it himself and liked it very much. He took me to many concerts because he wanted me to become a musician. But I did not want to become a musician.

JL :: Was he a musician himself?

AS :: No, not a professional one, but he wanted me to become one, so he taught me from early childhood. He sort of forced me to learn music, while my interest was more in other things. So he took me to many concerts with many of the famous musicians of India when I was a child, but as there never were any concerts of dhrupad at that time, or very few, I never heard it.

JL :: And it is North India we are talking about now, isn’t it?

AS :: Yes, because in South India dhrupad does not exist. Its is a North Indian style. So I heard dhrupad for the first time much later, in my twenties, when I was learning this other kind of music, khayal, which is a later kind of music. I heard dhrupad in a recording, and I heard it again and again, many many times, because it fascinated me. The voice, the quality of the voice, the depth, the grandeur of the style made me decide that I want to learn this.

The Dagar Family

The Dagar Family

JL :: And before that happened you had not yet decided to become a musician?

AS :: Even then, when I had heard this dhrupad recording, I was still not planning to be a full time musician. I was studying mathematics and physics at the time. But I became interested and was learning very seriously. I thought that I would keep it like a very serious hobby, and be almost as good as the professionals but not to earn money from it, because I did not know that it would be possible to do that.

JL :: But had singing always been important to you?

AS :: No, in my childhood I did not sing much. I played the sitar and some other instruments also, but I did not really sing much. The singing started later, when I went to university. After I had heard the dhrupad recording I told my khayal teacher about it, and he was of course very critical about it. He said:” It is very boring, there is nothing in it, it is just old and old fashioned.”

JL :: Is that a common view among khayal singers?

AS :: It is a common view in India generally, and especially among khayal singers and sitar players. And when I said: “But why, dhrupad is so great, it sounds so grand. Why did it go out of fashion?” He said: “The old has to make place for the new.” I was of course not at all convinced by what he said and kept looking for a dhrupad teacher. Then one day I saw in the papers that there was a dhrupad concert in Bombay (I lived in Bombay at that time). I was thinking about going to Calcutta, where I knew one of the Dagar brothers lived, and finding a job there, but then I saw this concert in Bombay. It was another one of the Dagar brothers, and he played the rudra veena. It was a very great concert. I really moved me. So after the concert I went up to him and told him that I want to learn dhrupad. Then he told me to come to his house the next day. I went there the next day. Then he told me that if I wanted to learn dhrupad I had to get up very early in the morning, at 4 am. in the morning. He told me to do some exercises and come back to him after a month.

JL :: So he showed you some exercises and said” go home and do this for one month”?

AS :: Yes, and for one month I did this. Then I went back to him. That is how my training started. But with him I learned only the very beginning things, because he died soon after.

JL :: So he was open minded enough to receive you as a dhrupad disciple?

AS :: Yes, and after he died I went to his younger brother to continue to learn. And with this brother I learned full fledged dhrupad, because I gave up my job. I learned full time for about ten years. Then I went to another brother of his, and then, finally, during the last five or six years, to the eldest brother of the whole family.

JL :: Is this the brother in the movie [Dhrupad: The call of the deep. A Film by Ashish Sankrityayan]?

AS :: Yes, he is the oldest at the present. In the family he was the third brother of eight. The two elder ones are dead now. The singing of the two older brothers impressed me the most. As professional performers they were really very good.

JL :: In the movie the brother that taught you is performing a certain ceremony. What is he doing?

AS :: He is tying a thread round the wrist of the disciple. Its is like a formal initiation, a formal acceptance of him as a student.

JL :: And at what occasions would you be able to hear dhrupad in India today?

AS :: You would hear it only at some rare occasions, at concerts mostly organized by the state, by the Indian government. And at some times, maybe, in a radio broadcast, but very rarely. In Delhi, the capital of India, you will hear a dhrupad concert once in two months.

JL :: And what kind of persons will be attending such a concert?

AS :: There will not be many people in the audience, because dhrupad is not at all popular in India any more. It is coming up again, slowly, and I think the lowest level of dhrupad interest was in the 1950’s, 60’s and 70’s. The 70’s was especially bad. From the 1980’s it has started to revive very slowly, because of the European interest. So there will be a few people in the audience interested in dhrupad, but this audience will not be very big.

JL :: Will there be old people, middle aged, young people?

AS :: Generally, in classical concerts, there will be mostly middle aged and old people, and very few young people. Very, very few.

JL :: So you travelled abroad to give concerts. Where do you usually go?

AS :: So far I have travelled to Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Belgium, France, Slovakia, Denmark, England, Scotland…

JL :: So it is mostly Europe then?

AS :: So far, outside India, I have given concerts only in Europe.

JL :: And what kind of organizations are organizing your concerts? What are your contacts in Europe?

AS :: Sometimes it is organizations that regularly do concerts, but where my concert will be their first Indian one. Then there are those that regularly do Indian concerts, like the Indo-German Society. Sometimes it is organized by private persons, who really like Indian music, and who like dhrupad very much.

JL :: So there is often a serious interest in Indian music among the organizers?

Ustad Rahim Fahimuddin Dagar tying the ceremonial thread around his disciples wrist. From a film by Ashish Sankrityayan: Dhrupad: The Call of the Deep.

Ustad Rahim Fahimuddin Dagar tying the ceremonial thread around his disciples wrist. From a film by Ashish Sankrityayan: Dhrupad: The Call of the Deep.

AS :: Both a serious interest in Indian music and an interest in dhrupad. The situation here in Europe is totally the opposite of what it is in India. In India it is khayal singing which is much more popular. Maybe not popular, I would say, but which gets the maximum benefits from the state funding. Because in India, all classical music is funded by the state, and the concerts are free for the audience. And these fundings go mostly to the sitar and khayal performances. In Europe it is the opposite. In Europe it is dhrupad that is more popular. Among Indian singers, the ones that visit Europe and America, are mostly dhrupad singers.

JL :: And the people that you meet at your workshops in Europe, and that want to learn more about dhrupad, are they professional musicians, or what is their relationship with dhrupad? Do you see some kind of pattern here?

AS :: So far I have only two students who are learning from me, but it is not dhrupad. They are learning the rudra veena, and they want to do it seriously. They have some musical background, they have either learned the violin, or some other European instrument before, and then they have become fascinated by dhrupad. I still don’t have in Europe a student who wants to seriously learn dhrupad singing, although I have had many, many students. Almost all the students I have had in Europe have been people who have been fascinated by dhrupad because of its sophistication, because of the whole philosophy underlying dhrupad singing, and of the technique of the voice. But they are not people who want to learn dhrupad full time. Many of them are European musicians, singers, even composers, cello players, who are doing their own music, and who learn dhrupad to enrich their own music. They want to understand the principles and concepts of dhrupad.

JL :: And to expand their own voices, perhaps?

AS :: There are many voice teachers who come to me.

JL :: I see. There is an enormous market in Europe and America for voice teachers. There are so many people that wants to learn how to sing, or to sing better. Search the Internet and you will find thousands of book on the theme” How to learn to sing”.

AS :: Of course dhrupad has a very sophisticated voice technique.

JL :: And that is why it is so interesting for voice teachers to learn some of these techniques. And they probably already have an artistic way of singing so picking up dhrupad full time is not a realistic option.

AS :: That is true. I have many students on a regular basis, but they are already musicians and they do not want to become dhrupad singers.

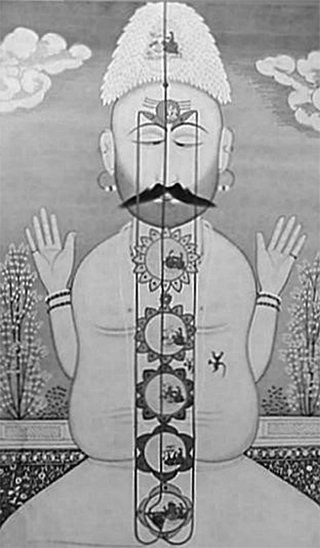

Chakras

Chakras

JL :: Today, at the workshop, when you were singing short phrases and we – the workshop participants – were trying to reproduce these phrases, the discrepancy between the colour of your voice and ours was enormous. Even if we would have been able to learn all the nuances of the melody and tempo and to make all the fine intonations in a correct way, we would still have lacked the essential quality of your voice merging with the sound of the tanpura. Why, do you think, is this so?

AS :: As I said, the method of singing dhrupad, the technique of using all these different positions, and the development of the voice and the resonances, all this requires many years of voice training. So you cannot expect people who are doing it for the first time to be able to do it. But if they did it regularly for some months, or a year, then, of course, you would notice the difference. They are not at all used to this kind of singing, or this kind of music, to these ornaments, these complex micro-ornaments, and they do not know how to use he voice to do this.

JL :: It has been established by linguistic scientists that if you acquire a foreign language after the age of twenty, approximately, you will never be able to speak it without an accent. It is impossible, no matter how hard you try. Could it be a matter also of this inherent linguistic limit that makes it difficult for us to reproduce your kind of voice?

AS :: It is difficult for Europeans because in European music the notes are very straight, you do not explore much this whole space between the notes, while in dhrupad the notes themselves are fluid, and there are ornaments where the notes are not used in a straight way. There are also a lot of silent notes. People are not familiar with this, and not familiar with using the voice like this. But given enough time these persons will of course be able to do it. A few Europeans have tried to learn dhrupad, and they have attained some standard, but then again they have not lived in India for a very long time, just a few years. If a European wants to learn dhrupad and do it for, let’s say, ten years, and spends a lot of time with a teacher, it is entirely possible. I have these two students of the rudra veena who play very, very well. In some time, they will even be able to do concerts.

JL :: That is very reassuring! Yesterday, at the concert, and also today, during the workshop, I noticed that sometimes it is as if your voice is doubled. This other voice is almost like an echo, but too close to your voice to be an echo. Is it the tanpura that produces this effect? Do you know what I am talking about?

AS :: The voice that I use employs all these resonances of the body, the navel sound, all these regions from navel to head, and all these channels and resonances are used and gives the voice a different quality. Sometimes this voice will sound like in a space with an echo. It is the resonance which is creating this. Another thing is that because the inner resonances of the body are developed in dhrupad singing, the voice acquires a lot of overtones. The overtones become prominent. So when we sing the prominent overtones are always there. While I am singing the overtones are also making a melody.

JL :: Do you use the resonance chambers of the tanpura? Can you hear your own voice resonating in them?

AS :: The tanpura always responds to the voice.

JL :: Does it respond more to certain notes than to others?

AS :: I cannot say, but it responds to the voice, and it is important to tune it properly, because then there is an interplay between the two.

JL :: It is sometimes difficult to know if it is the voice or the tanpura that is producing certain sounds.

AS :: The singer who sings with the tanpura will subconsciously and automatically adjust the overtones of his voice to the overtones of the tanpura.

JL :: I also have the impression when you sing that the source of the voice moves its location in space.

AS :: Yes, and sometimes it can be as if the voice comes from different parts of the room. It is because when the resonances change, it will appear like that. This is not done to create an effect, but it is a fundamental requirement of the music itself, of its laws and principles. This music demands this, it is not done as a gimmick or an effect.

JL :: In your article which can be found on the internet,” Dhrupad as in Dagar Tradition”, you write that dhrupad is essentially a spiritual pursuit. Can you dwell on that statement little bit?

AS :: Dhrupad has its origins in the vedic chantings, which was a purely religious and spiritual practice. Vedic shlokas, texts, were chanted using the same kind of voice technique as in dhrupad. These chantings were done with only one or two notes. It was more like a meditation, or a worship. So dhrupad evolved from that, and although it is now a musical system, an art form, when you sing it, when you use this kind of yogic voice technique, the whole purpose of singing is not just to demonstrate some skills and to entertain people, but to reach a certain internal state, to attain a complete dissolution or identification of the self with this sound. Your self and the sound become one. This is something that comes from Indian philosophy. So when the dhrupad singer sings, his concentration is wholly on the sound that he produces. This meditation on the sound becomes like a worship. The sound itself is the object of contemplation, and then you become one with that object. And besides being this meditation and worship, it is also an art form with a lot of artistic beauty. This is why dhrupad has declined in popularity the last few hundred years, because even if it is a high art, it does not strive to entertain or astonish the audience with fast and difficult acrobatic passages…

JL :: …like in khayal singing?

AS :: …yes, like in khayal singing. It is a difficult art, but the difficulty lies in all these subtle things with the sound, the resonances, the notes, the very subtle things that the singer does with the sound.

JL :: Would you say that it is also a spiritual pursuit to listen to dhrupad?

AS :: Yes, this is why dhrupad is not for casual listening, and that is also why it is difficult to propagate dhrupad by the sale of records and CDs, because most listening to records is a kind of casual listening. People are listening to the music while eating or sending an e-mail or just thinking about something else. The music is in the background. But dhrupad is not for this kind of casual listening. Because the dhrupad singer is performing this complete identification with the sound, the same thing has also to be done by the listener. In a successful dhrupad performance, where the singer really does achieve this complete identity with the voice, the music and the sound, then the same inner state is created in the listener.

JL :: Even though the listener does not sing?

AS :: Yes, because all these inner resonances in the different centres – the chakras – of the subtle inner body, they resonate in the same way in the listener. So the effect is not only on the level of the hearing, but also on a deeper, subconscious level.

JL :: Does the listener have to pay the same attention to where the sound resonates?

AS :: No, that is not necessary. The listener just have to listen with attention, then it will automatically get into him.

JL :: Just one final question, then. Is there any other kind of music in any part of the world, that you feel dhrupad is related to?

Hildegad von Bingen

Hildegad von Bingen

AS :: Dhrupad, and dhrupad singing is of course related to a lot of the sacred music of the world, and especially the medieval music of Europe. In some ways, it is very similar.

JL :: The Gregorian chants?

AS :: The Gregorian chants, the songs of Hildegard von Bingen. The structure of that music, the melody, the way the phrases are built up, the principles are similar to that of dhrupad. You can even have concerts were both of these forms are presented.

JL :: Have you participated in such collaborations?

AS :: Yes, I have done concerts where another singer sang songs from Hildegaard von Bingen, then I sang similar dhrupad improvisations.

JL :: Thank you very much. I hope we will see and hear much of you in Europe in the future.